Anat

While doing some background reading on Bronze Age Canaanite religion and mythology I came across Anat, a bloodthirsty huntress and warrior goddess whose predilection for violence almost brings catastrophe in one story and in another helps save the world from disaster. Unruly, destructive, passionate and disdainful of authority, she stands out among the other goddesses of her pantheon as a being of spirit and vitality, and seemed the perfect subject for a novel aimed at bringing the myths of the ancient Canaanites to life.

From the Ruins of Ugarit

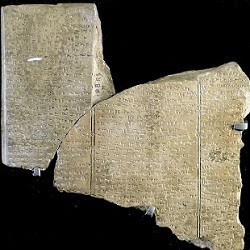

The myths relating the deeds of Anat and her fellow deities come from a place called Ugarit, a once-wealthy and thriving city on the coast of modern Syria that was destroyed around 1200 BCE. Its ruins were discovered in the late 1920s and the subsequent archaeological excavations have yielded a rich haul of clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform writing. Many were written in the Babylonian and Hittite scrips and languages, but many more were in the alphabetic scrip used by the natives. Alongside hundreds of personal letters, legal and administrative texts, lexical lists and descriptions of temple rituals were a number of epic poems and myths featuring gods such as El, the creator; Baal, god of war, storm and crop fertility; and Ashera, El's wife — all of whom can be also found in the Old Testament.

One of the poems, entitled Aqhat by modern scholars, introduces us to a man named Danel, who is a king or ruler of some kind. He is also miserable on account of having no male heir "to guide his footsteps when he is drunk and shut the jaws of his abusers". El, his patron, hears his laments and blesses him with a son, the eponymous Aqhat. Danel is overjoyed; he goes about his palace laughing and smiling. Then Anat becomes involved in the tale and events take a decided turn for the worse.

The longest of the poems, spread over six badly damaged tablets, is the Baal cycle, an epic describing the titular god's contests first with Yamm, who represents the destructive power of the sea, and then Mot, otherwise known as Death. Anat plays a key role in Baal's struggle, particularly at the end.

My novel will be principally a blend of the two myths, along with parts of Babylonian and Hittite tales, and even bits plundered from Hebrew scripture.

Fitting Humans into the Picture

As well as reading the myths themselves and as many supporting academic papers as I can find I also need to build the world inhabited by the mortal characters, among whom are Danel, who may have been a king, and his plucky daughter Pugat. Almost no information is given in the poem about their city's geopolitics — indeed, even its name is only conjectured. So I have decided to place them in the same historical context as the tablets themselves, namely late Bronze Age Syria, when civilisation was collapsing under the weight of drought, famine, disruption of trade routes and repeated foreign invasions.

Gods and Mortals

In the Aqhat poem a human grows from childhood to near-adulthood, while the Baal epic appears to take place over a few seasons as the gods see it. How to combine the two timescales into a single narrative? Partly inspired by Christopher Nolan's film Dunkirk and partly by the myths of a place called Glorantha, I decided to have time pass at different rates in the mortal and divine realms. The gods lead a largely timeless existence, repeating the same actions over and over — unless some crisis or disruptive element, such as Anat, forces a change in their behaviour. They receive worship but are largely unaware of mortals as individuals. None of this is explicitly stated in the myths, but it does provide a convenient mechanism for explaining, among other things, how the gods, all-powerful yet with human desires and flaws, manage to avoid going mad with boredom as the aeons drag slowly by. Further justification comes from the fact that some scholars believe ancient Mesopotamians — and, I assume by extension, other peoples in the ancient Near East — perceived time differently from us.

Another difficulty is capturing the feel of the relationship between Canaanite gods and their mortal worshippers. The atmosphere of the myths is closer to that of the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh than Homer's Iliad (or, if you prefer, the film Clash of the Titans — by which I mean the original, with its incredible Ray Harryhausen special effects). The gods of the ancient Near East come across as being less petty and spiteful than their Greek counterparts, despite being equally capricious (and equally lethal when angered). They do not play games with the lives of mortals, maneuvering them like chess pieces and guiding their destinies for good or ill; rather, they tend to keep their distance and communicate with mortals in dreams, only rarely becoming directly involved with their lives.

Among the poems from Ugarit only two — Aqhat and Keret (another tale about a king with no heir) — feature gods interacting with mortals to any significant degree, often to said mortals' detriment. Like those of the various Mesopotamian pantheons, Ugarit's gods are to be appeased more than loved (it is, I think, no coincidence that the Old Babylonian verb palahum means both "to worship" and "to fear"); their goals and concerns are largely mysterious to mortals, and their manifestations are as unwelcome as they are terrifying.

To me this divine ambivalence towards humanity is similar to that found in the Hindu epic The Mahabharata, in which a feud between two sets of cousins in a family of demigods erupts into a war that claims the lives of over 1.5 billion people. Yet to the gods the whole episode is just one more phase in their aeons-long conflict with the world's demons, and the terrible events on the battlefield -- the carnage and the mayhem, the countless individual tragedies and the vast scale of human suffering -- are merely collateral damage.

Setting Mandrakes in the Dust

Although Ugaritian was deciphered within a few years of Ugarit's discovery — thanks to its closeness to Biblical Hebrew and other ancient Semitic languages and the fact that it was written in a simple alphabet script — there is still much disagreement over the interpretation of a number of passages in the myths.

For a start, Ugaritic was written without vowels, punctuation marks or spaces between words. Also, the tablets are in such a poor state of preservation that many of the signs are mere impressions in the clay and whole chunks of texts are missing.

It does not help that we lack the background knowledge that the native hearers and readers of the texts took for granted. Much of the mythic symbolism found in ancient literature we simply do not understand, and there are many idioms, euphemism and turns of phrase that, to modern scholars thousands of years later, are incomprehensible. Also, even apparently well-understood words can be used in unexpected ways. To give two examples from other languages where such use is known, in Sumerian love poetry the word for lettuce can also refer to a woman's labia, and in Akkadian "to set one's ear" means to decide on a course of action.

In the Baal cycle there is a scene where the god sends a message to Anat, telling her to calm down and stop slaughtering her enemies. One modern translation has Baal exhorting Anat to "Remove war from the earth; set love in the ground". An alternative translation reads "Place bread in the earth; set mandrakes in the dust". The meaning is clear, but the details are not. Why bread and mandrakes? Are they ceremonial offerings whose significance escapes us, or are they the material components of a fertility ritual (something of an obsession with early scholars of Ugarit)? Or perhaps the first rendition is closer to the original, with its more direct interpretation.

Regardless of how they differ in their details, the many translations of Ugaritc poetry all give a sense of the power of the Baal epic, and the humour and irony contained in some of the other stories. This is a body of literature that not only predates the Old Testament by centuries but had a direct effect on shaping its contents. Even disregarding its influence, its sheer strangeness and imaginative scope, which rival that of modern fantasy literature, make it well worth reading.