The Road to Kadesh

I began writing The Road to Kadesh one evening in an Indian restaurant. As I sat sipping my beer and waiting for my food to arrive the vision of a chariot battle began to unfold before my inner eye, in a cinematic riot of dust, noise and violence. Immediately I scribbled a hurried draft of the novel's opening scene, filling an A4 sheet of lined paper with tiny biro writing. I still have that turmeric- and beer-stained piece of paper somewhere. From that opening battle the novel grew, the plot developing as I wrote. I had no plan; all I knew was that I wanted the battle of Kadesh to feature somewhere.

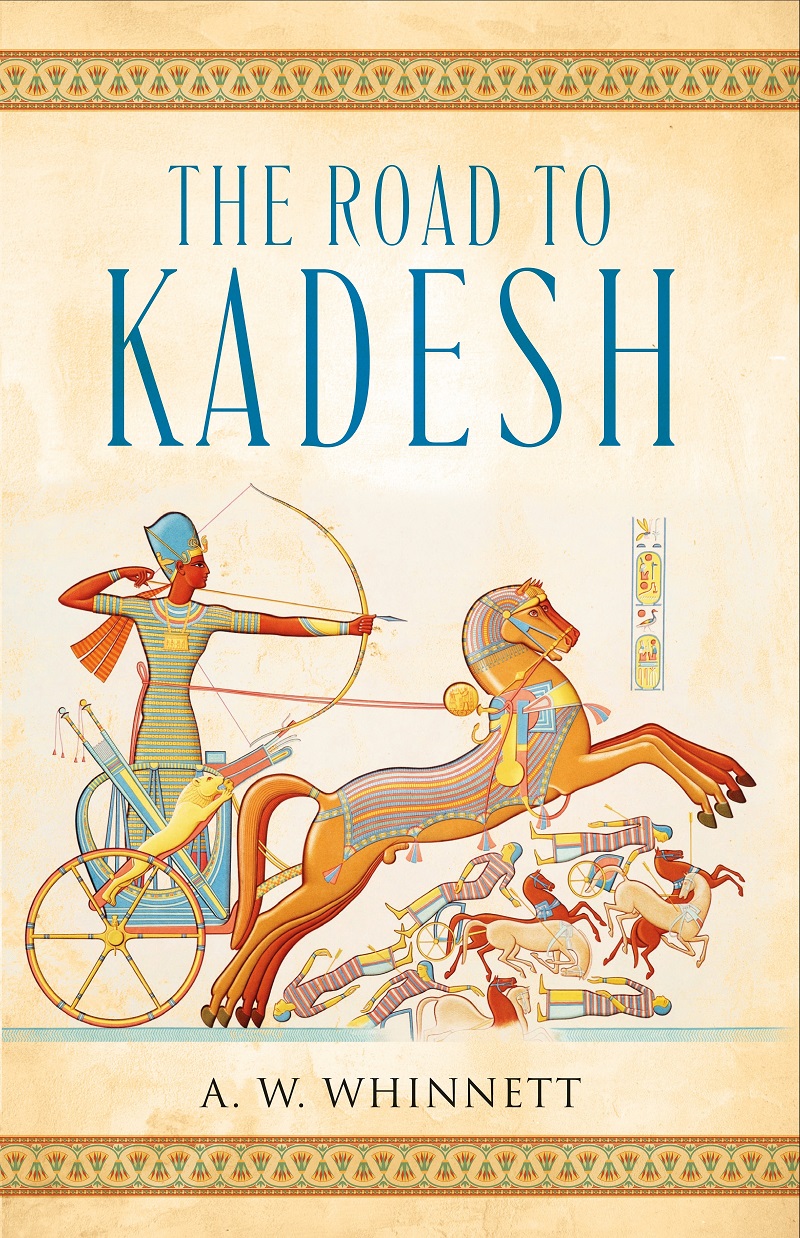

The Road to Kadesh is not the first novel I have written but it is the first I am selling, possibly because it has the best title. There are links on the right showing a few websites where it can be purchased. A cover image is shown above; taken from the Kadesh inscription at the Ramesseum in the Theban Necropolis, it depicts Ramesses II in his chariot slaughtering his way through a horde of floundering Hittites. According to New Kingdom Egyptian ideology, if foreigners were left to go about their business unchecked famine would stalk the land, the earth and sky would mix and the sun would no longer rise. So Ramesses, according to his lights, is simply doing the world a favour by killing some of its inhabitants.

If you read the novel and like it do please leave a review on Amazon or Goodreads, so I know what went right. It may encourage me to work on a sequel. Or perhaps something else entirely (see my Anat page).

Some Notes on the Book

In all my writing I try to present the historical world from my characters' point of view, avoiding as much as possible the imposition of my own standards and opinions (although there are limits: see my notes about this under Musings). This means, among other things, writing about their gods as if they were real.

Most of what is known about the religions of the ancient Near East, Egypt included, concerns the state cults, with their vast temples staffed by armies of priests performing elaborate rituals designed to keep the cosmos running on an even keel. By contrast, the spiritual beliefs and practices of commoners are still poorly understood, although the scholarly consensus seems to be that much of it involved ancestor worship and the veneration of local demigods. Where there are gaps in our knowledge I have invented freely, and have even once or twice contradicted established facts where I thought it would better fit the story. In other places, where the findings of archaeologists or my own imagination failed, I have relied for inspiration on the religious practices and myths of a rather remarkable place called Glorantha.

Unlike Egypt, little is know about the state religion of Amurru beyond the names of a few gods. To make up for this lack I have transplanted the entire pantheon from a place called Ugarit, a Canaanite city on the Mediterranean coast 100km or so north of Sumur. There are many similarities between the religions of Ugarit and what would later, in the Iron Age, become Israel and Judah, and since Amurru is located somewhere in between these places I feel that my choice is justified. (For more information about Ugarit see my Anat page.)

The drunken ritual that takes place in the novel is my own invention, inspired by two historical sources. The first is the existence of an institution called the Marzeah — a kind of Bronze Age wine-drinking club that is mentioned in a range of texts from various times and locales in the West Semitic world, including the Old Testament and some of the clay tablets found at Ugarit. One of its purposes may have been to allow the leading men of a city to gather in private and discuss business; alternatively, it may have simply been an excuse for the menfolk to go on an extended bender without their wives and children getting in the way. The second is a myth concerning the god El, who was the head of the pantheon at Ugarit (and, incidentally, is also one of the main gods of the Old Testament, where he is sometimes known as Elohim, the all-powerful sky wizard who creates the Universe in six days). Anyway, in the Ugaritic myth El and the other gods hold a feast in which they eat roast meat and drink wine — lots of wine. El becomes so drunk that he has to be carried home by his companions, whereupon he collapses "like the dead" and soils himself. The tale ends with what some think is a recipe for a hangover cure.

Turning now to the historical events depicted in the book, it is known that Ramesses campaigned in Canaan in the fourth year of his reign. Unfortunately the monuments he set up to record his deeds are so weathered as to be illegible, so we have no idea exactly where he went or what he did. The campaign was very likely nothing more than a flag-waving exercise to discourage rebellion and bring wavering vassals into line, and the novel's battle against the army of defiant Amurrites is pure invention on my part.

Concerning events in the west, it is known that the Libyans became a serious threat only in the reign of Ramesses' son, although during the period the novel is set they were making enough of a nuisance of themselves to prompt Ramesses to begin constructing a series of forts along Egypt's western border.

The Battle of Kadesh

The only substantial account of the battle of Kadesh we have is Ramesses' own, repeated with only minor variations at five sites along the Nile valley. Each account comprises two large blocks of text (the so-called poem and bulletin) and a captioned set of images, and only when all three are taken together do they form a narrative whole. Noteworthy is their honesty in describing how close Ramesses came to disaster after underestimating, and being outwitted by, his Hittite foes.

According to both the poem and the bulletin it was he alone who saved the army, fighting single-handedly against a force of 2500 Hittite chariots. Some historians accept this figure at face value; others of a more practical bent point out that it would have taken over two days for that many chariots to cross the ford at the Orontes tributary, and the Hittite assault was more likely a reconnaissance in force comprising a few hundred machines that blundered into Re division on its way to the Egyptian camp.

The traditional view is that the battle lasted for two days. However, the accounts describe Ramesses' victims on the second day as "rebels" rather than the "fallen men of Hatti" he fought on the first day. This has lead some Egyptologists to argue that Ramesses, rather than renew the fighting, spent that second day decimating his army as a punishment for cowardice — which was good for me, since having to describe yet another battle at that point would have brought on a debilitating case of chariot fatigue.

The identity of the relieving force that beat back the second Hittite attack and saved Ramesses is a matter of some debate. They are not mentioned at all in the written record, appearing only in the pictorial account as a mixed unit of chariotry and infantry, and are named in a caption as the Ne'arin. A common assumption is that they were a fifth division of troops raised at Amurru and dispatched to link up with Ramesses at Kadesh. Perhaps they were scheduled to arrive simultaneously with the main body; if so, it shows a degree of coordination between disparate parts of the Egyptian army that would have had Napoleon chewing his hat in envy, and means that either Ramesses was extremely fortunate in the way events turned out or that he was, indeed, a god.

Change is Sometimes For the Good

My version of the battle is as accurate as I could make it and only veers from the scholarly consensus in a few places. For the most part I have been deliberately vague about the numbers of chariots present, suggesting in places that only a few hundred Hittite machines were involved in the attack on the Egyptian camp, and elsewhere describing the dust, noise and chaos of a clash between thousands on each side. I also, somewhat mischievously, made Ramesses' chariot driver Menna admonish the pharaoh for wavering near the end, whereas according to the monuments it was Menna who needed his back stiffening. I also compressed time by about twelve hours or so by having the Hittite attack take place on the same day that Ramesses and Amun division arrived at the camp.

I have used the term Canaan to describe the entirety of the lands along the eastern Mediterranean, a region the Egyptians called Retjenu. Elsewhere I chose commonly-used geographical names, rather than consistently use solely Egyptian or local terms. One or two changes to geography were necessary to keep the story moving; in particular, I moved the Bahariya oasis closer to the Delta and made it representative of the western oasis complex as a whole.

Anyone wishing to follow the flow of the battle might like to consult a map, of which there are a number available online (and I apologise for being too lazy to draw my own). The available maps come in two flavours, depending on how one draws the course of the waterways. One set shows the initial Hittite assault crossing the Orontes itself; the other has them crossing at a ford on the Al-Mukadiyah tributary. I chose the latter, in conformity with most scholarly accounts.

The Egyptian World View

Pharaoh was a living god and Egypt was the centre of the world, a perfect land created during the First Moment by the great god Amun. Beyond the land's borders was uncivilised chaos populated by vile Asiatics, fallen men of Hatti, and wretched Libyans and Nubians — collectively known as "the Nine Bows", the number nine being another way of saying "many" or "countless".

The governing principle in any Egyptian's life was Ma'at, a term embracing a wide range of concepts including peace, stability, justice, good governance, prosperity, and a whole other raft of desirable things. Ma'at was also a goddess, often represented by a feather. When Ma'at was strong Egypt prospered, the pharaoh was wise and just, and foreigners were kept in their place; conversely, a weakening of Ma'at could lead to famine, disorder and foreign invasion. In a muddling of cause and effect typical of the ancient mind it also seemed to work the other way around, in that Pharaoh's actions could strengthen Ma'at or, if he ruled unwisely, could diminish it to a dangerously low level.

All of which helps explain why New Kingdom Egypt was such a highly militaristic society. Of course, strategically it made sense for them to conquer as much of Canaan as possible to create a buffer between Egypt and any potential invaders, most of whom came from the east. But Ma'at also had to be maintained, and to that end the pharaoh was under a religious obligation to suppress the foreign menace — primarily by slaughtering all and sundry in battle and enslaving the survivours.

Late Bronze Age Doublethink

The Egyptians' exceptionalism and xenophobia, not to mention their creation myths, made Egypt the foremost nation on Earth, with all other nations populated by Ma'at-less barbarians, there to be massacred, enslaved or ignored at will. But reality, as it so often does, had to intrude and spoil the conceit. The Hittites, Babylonians, Assyrians and Mitanni were great powers on a par with Egypt, and their kings were every bit the equal of Pharaoh. These kings — Pharaoh included — regularly exchanged letters in which they addressed each other as "brother", wished each other well and asked after the health of their brothers' kingdoms, spouses and chariot horses. They also exchanged gifts, or begged shamelessly for gifts to be sent, made peace treaties and extradition agreements, and even dispatched their daughters to each other's harems.

How then did the pharaoh and his ministers reconcile these two contradictory world views, in which on the one hand Egypt reigned supreme, yet on the other was only one of a number of equally powerful states? In the novel I decided to have Ramesses largely believe his own propaganda and act as if he were indeed Egypt's living god, and gave his ministers and generals the job of reinterpreting his decrees to better match the reality of their situation.

Then there is the matter of how the Egyptians reconciled their xenophobia with reality. The cities of Egypt were highly cosmopolitan, hosting not only enslaved prisoners of war but also labourers, craftsmen and specialists from all over the Mediterranean world. For instance, archaeologists have found evidence that a team of Minoan artists was employed by the pharaoh Thutmosis III to decorate one of his palaces; they covered the walls in Cretan-style friezes. And in common with all other contemporary civilisations, the Egyptians readily assimilated other cultures' deities into their own pantheon, reworking their myths to make them fit. How did the locals square the presence of so many foreigners, and so much foreign influence, with their belief that they were a menace whose very presence would stop the sun from rising?