On Science (By Which I Really Mean Physics)

I am a theoretical physicist by training and still maintain an interest in the subject. So I am going to write about it here.

This website's main purpose is to provide background notes for my historical novels, which are all set in and around the ancient and classical Near East, when belief in God or gods was stronger than it is now and people's lives were ruled by their superstitions. All of which is a world away from the harsh reality of... well, reality, and the way modern physics describes it.

I suspect that physics, more so than other sciences, is perceived as being somewhat dry and dull. Which is a shame because there is poetry in physics, and a beauty that can take one's breath away.

Physics is Awesome

Physics is awesome. No other way of seeing the world can match its ability to describe, explain and predict the behaviour of matter and energy. We (by which I mean humanity as a whole, my own contribution being close to negligible) can accurately describe the physical world at an astonishing range of distance scales and energy densities, and for the first time in human history make sensible, rational statements about the origins of the Universe itself. All of which is remarkable given the fact that modern physics is only a few centuries old.

We have built particle accelerators to probe the structure of matter at scales smaller than atomic nuclei and orbiting telescopes that can see galaxies forming almost at the beginning of time itself. And experiments on quantum mechanics are revealing more and more about the sheer weirdness of reality at the fundamental level, properties we may one day exploit to build computers of incredible power. Yet there is so much about the Universe we do not understand, and doubtless an awful lot more that we don't know we don't know. We are living in a golden age of scientific discovery — interesting times to be a physicist.

What Physicists Do

Experiments are good and necessary — after all, this is science, not theology — but to a theoretical physicist it is in the theories themselves where the real beauty lies. Presenters of science documentaries sometimes get all emotional when describing the cosmos in all its glory, partly on account of the very elegant laws of physics we have devised (or discovered, if you prefer) to describe it.

Physics is "written" in mathematics, which is a bit like a language in that it can make statements about things, although it also has a number of unique properties, the most useful of which is a built-in set of rules that allow true statements to be derived from other, often simpler, statements. Pure mathematicians exploit this property in their daily work: they start by writing a set of assumptions (otherwise known as axioms) and "unpack" them using the rules of mathematics to derive consequences (in other words, prove theorems). In doing so they build beautifully complex structures that explore the relationships between sets of highly abstract objects — cathedrals of thought, if you like.

Theoretical physicists use mathematics to describe reality. Physical quantities are represented by mathematical objects, the art being to match each quantity with the correct mathematical object. The laws of physics these quantities obey are then taken to be the rules of mathematics obeyed by the chosen objects. Mapping the results of mathematical manipulations back onto the physical world allows us to predict not only the behaviour of real systems but also to explore the structure and nature of physical reality itself. And the process works remarkably well, having correctly predicted the existence of a range of previously unknown phenomena and objects. This apparent correspondence between mathematical and physical reality is one of the many unsolved mysteries of the Universe.

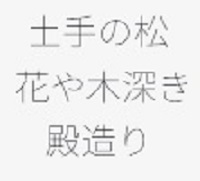

Haiku

Haiku is a form of poetry that first appeared in Japan in the 17th century. A single haiku comprises three lines, traditionally of seventeen syllables in total, and captures the essence of a particular fact or observation about the natural world. The idea is to express the observation as elegantly as possible; I would not be surprised to learn that there is some connection between haiku writing and Japanese calligraphy. An example of a haiku is shown nearby. It was composed by Matsuo Basho, one of the form's pioneers, and in a handful of symbols describes the initial impression one has when seeing a thick tangle of forest.

The Poetry of Physics

But what does an old Japanese art form have to do with physics? Well, imagine writing a haiku about a forest, not in Japanese kanji but in mathematics. This mathematical haiku expresses some essential fact about the forest's gross properties. But because it is written in mathematics we can unpack it, using the language's built-in rules, and in doing so we discover more haiku, each describing, elegantly and succinctly, a previously unknown animal that lives in the forest. Unpack these haiku and we find a whole lot more, telling us about the animals' attributes, origins and behaviour.

In a similar way physicists construct theories that express, in the simplest and most elegant way possible, the relationships between fields and the distribution of their sources. Using the rules of mathematics these theories are then "unpacked", hopefully revealing new truths about the Universe — anything from the properties of new kinds of fundamental particles to the structure and behaviour of space and time itself.

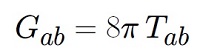

An example. My specialisation was general relativity (GR), a theory devised by Einstein more than a century ago that describes gravity in geometrical terms. The theory's field equations are shown nearby — a haiku, if you like, relating the curvature of spacetime (encoded in the symbols on the left of the equals sign) to the distribution of matter and energy (appearing on the right), all captured in a mere handful of symbols. It may not look like much, but the left hand side in particular represents an extremely complicated mathematical object, and to "read" it one needs to be proficient in a branch of mathematics known as differential geometry.

For over a hundred years theoretical physicists have been exploring GR's complex structure, unpacking it to reveal previously unknown objects and phenomena, including black holes, gravitational waves and the expansion of the Universe — none of which were know to exist or occur at the time the theory was formulated, not even by Einstein himself.

Maybe I'm biased, but I think GR is the most beautiful and elegantly-formulated of all our theories of physics. It is as rich and complex as the greatest works of literature or music; indeed, it is one of humanity's crowning achievements. And I think it's a shame that, on account of this very complexity and the amount of study required before one can read it, the theory is denied a wider audience.